THE BOOK OF JOB points out at least one trouble that we bring upon ourselves. That trouble occurs when we think, either because of some imagined worthiness in mankind, our cleverness and self-sufficiency, or even from our being saved by grace, that we should be immune from natural calamity or purposeful wickedness in the present world.

In chapter 5, Eliphaz tempts Job to believe that he should be experiencing goodness and security in this present, fallen world, which is only promised in the “new heavens and the new earth,” which are spoken of in both the Old and New Testaments.

“You will laugh at destruction and famine,

and need not fear the wild animals.

For you will have a covenant with the stones of the field,

and the wild animals will be at peace with you.

You will know that your tent is secure;

you will take stock of your property and find nothing missing.”

Can we fix the world?

Now, on the one hand, theologians from Irenaeus, Augustine, and Calvin to Abraham Kuyper, N.T. Wright, and C.S. Lewis have pointed out that, yes, we can indeed work to undo some of the effects of the fall in our present day, and it is indeed our calling to do just that in our own admittedly small way.

But to take that and hold it up as an expectation of goodness, of temporal blessedness, is a gross error. It flies in the face of God’s justice against sin and sets us up—especially on a personal level—for repeated disappointment.

But don’t we deserve some good?

Should we anticipate any good in our lives? After all, we are a fallen race. As the Westminster Catechism says, we are cursed by “the guilt of Adam’s first sin” and are subject to all the pains and penalties of that sin. And then, if that weren’t enough, we add our own transgressions to the mix, and thus, we are “liable to all miseries in this life, to death itself, and to the pains of hell forever.” That is one load of misery!

So, should we expect good times throughout our lives? I don’t think so. To put it another way, perhaps we should be more surprised when something good happens to us rather than when something bad happens.

Yes, Job is a special case. He was not only subject to the results of original sin and his own transgressions, but he was also a special subject of an interaction between God and Satan in the eternal realms.

God tested others, such as Abraham, Joseph, Moses, Daniel, and his friends. However, many of these trials resulted from a lack of faith or moral failings on their parts. Job’s experience was unique: It is recorded explicitly as an cosmic wager of sorts, a direct confrontation between God and Satan.

Job’s experience is also unique in its severity and comprehensiveness, involving his wealth, children, health, and social standing all at once. Furthermore, in its lack of explanation, it was unlike other biblical figures—persons who often knew the purpose of their trials. Finally, we are given a rare glimpse into the extensive philosophical and theological discourse between him, his friends, and ultimately, God himself.

So, in the final analysis, it may be best for us to realize that, when God seems to be hiding his blessings from us for a time, we should keep in mind that he is also hiding his wrath.

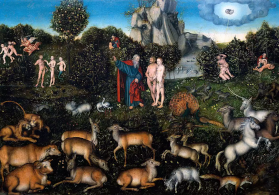

Image: The Garden of Eden, Lucas Cranach the Elder (1530)

Good stuff, Curt. We tend to make the good things normative, what is to be naturally anticipated and, on some level, owed to us. And the bad things, we see them as so unnatural, so unexpected, and perhaps indicative that there is perhaps no God or that he is simply not that good if he lets such things happen.

Thank you, Jonathan. My hope throughout this blog/book is that we adopt a more realistic/biblical faith that would keep us from immediately abandoning it (or having to “reconstruct” it) in the face of trials, troubles, and tragedies.